The following is excerpted from The Musician’s Guide to Recording, a free PDF full of great practical tips, advice, and wisdom on the recording process. Click HERE to download the complete guide for free.

The following is excerpted from The Musician’s Guide to Recording, a free PDF full of great practical tips, advice, and wisdom on the recording process. Click HERE to download the complete guide for free.

PAUL WESTERBERG

“When the title comes, it all falls into place, because the title sets the mood. For instance, ‘Mannequin Shop’ was a silly title that came from a People magazine article about plastic surgery. Once I decided I was going to write a disposable little pop song about something current and ridiculous, it just flowed. If I hadn’t come up with that idea, it would have been a laboring effort. But once you make up your mind that this is going to be a cute one, no two ways about it, you can go for it. Now, if it’s a rock and roll song, I’d say get your gut feeling out whatever it is. Even if you think, ‘Oh, I can’t say that,’ go ahead and say it. Spit it out, and if you’re going to be a fool, be a fool.”

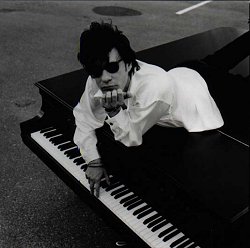

CHRIS CORNELL

“Sometimes personal lyrics can be endearing and cool, and make you feel close to the writer. But, a lot of times, you get this feeling of ‘Why do I care? So you had struggles with your relationship—good for you. Everybody does. F**k off.’ I’d rather go more towards the Syd Barrett school, and write about shoelaces and banana skins, and make it all seem congruent in this weird fantasy world that makes you want to go there when you get off work.”

NEIL FINN

“I like to leave as much as possible in the early stages to a kind of unconscious process. I’ll find a place where there are no distractions, get into a dreamy state, and just mess around with chords and chord sequences. Eventually, little melodies come out, and it’s really a matter of recognizing what’s good. You have to be careful not to think too much about things. For example, my wife—who doesn’t write songs— will get in a buoyant mood, and just sort of sing along with some chords I’m playing. And, sometimes, the melodies she sings are as good as anything I could write. I think that’s because she’s just kind of going with the moment, and letting something come out that’s very unconscious. And that has to be the beginning of songs. If you’re too disciplined in the early stages of the writing process, then there’s a good chance your songs will sound a bit flat or uninspired.”

RAY DAVIES

“I recommend minimalism wherever possible. If something is simple, and the observation is true, why burden it with a melody that takes it into some other realm? You must find an emotional moment in a song, as well. A film can only go for about seven minutes before it must have an emotional moment on the screen. Otherwise, the audience gets bored. With songs it’s the same, except that you have three minutes— not 90 minutes—to make everything happen.”

ROBBIE ROBERTSON

“I try, to the best of my ability, not to think the song to death. The main criteria for me is if it’s working on an emotional level. If I’m writing a song, and something is happening that has the potential to give me goosebumps, then I’ll want to pursue that path. I got into music in the very beginning because I heard music that gave me chills. And I thought, ‘I want to do that. I want to give somebody else chills!’ So, for me, it’s all about discovering the emotions in the music.”

PAUL WESTERBERG

“You may think you have to be really aggressive or flashy on the guitar, but, more often than not, that gets in the way of what the song is saying. You have to make up your mind: ‘Am I going to be a player,or is this going to be a song?’ Don’t worry—there’ll be a spot in the song for someone to show off—whether it’s you or another guy.”

LYLE LOVETT

“There are varying degrees of success when you’re trying to express an idea. I think the most important ingredient in a song is the idea, or what you’re trying to say. If you have a clear idea of what you want to say, then you know when you have said it, and the song is finished.”

CHRIS WHITLEY

“An ‘intentional’ songwriting approach, is where you pick a topic and then write about it. When you come at a song like that—with a presupposed literal intent—you block yourself, and your subconscious can’t speak. Howevever, when you pull something from your subconscious, you get visceral metaphors, rather than literal or literary metaphors. It’s not exactly a new idea. I think Talking Heads explored it on Remain in Light, and Bowie was definitely making up lyrics and melodies on the spot when he recorded Scary Monsters. This approach leaves you open to discover what really works on a soul level.

“For example, experienced writers often disregard simple chord progressions as boring. But sometimes a vocal melody can sit on top of a simple progression in a way that makes the song special. It goes beyond the literal meaning of the lyric or the catchiness of the hook to that elusive thing—I call it ‘resonance’—that makes lullabies and gospel music so timeless. I also use subconscious writing as a way to connect with the listener, because I think the stuff that resonates with people is pretty universal. It’s like, how much can sex change in a couple of thousand years? Culture can change, but, on a soul level, people need the same things.”

Songwriting Tips from the Hitmakers, Pt. 1

Songwriting Tips from the Hitmakers, Pt. 3

Sell your hit songs on CD Baby, iTunes, Amazon, Rhapsody, and more!