A well-crafted set list can mean the difference between a superb, decent, pedestrian, or down-right awful performance. Hand-in-hand with talent and presentation (attire, lighting, segues, etc.), a well-crafted set list can help a novice come across as professional, and a professional come across as remarkable.

When crafting a set list, the following elements are essential to keep in mind:

- Audience

- Key

- Tempo

- Feel

- Transitions

- Timbres/Voice(s)

Audience

Who are you performing for? What do they expect? Will the audience be listening, or will they be dancing? Your material should be chosen appropriately. A listening audience need not be exhorted to “Get up out of your chairs!” In fact, if the venue is not dance-appropriate, getting people up out of their chairs to dance might get you 86-ed from that venue forever. Be aware of what the venue expects and design your set list accordingly.

Keep in mind that a dancing audience is more likely to respond best to songs with simple lyrics and anthemic, sing-along choruses. (“I wanna be sedated!” “I fight authority!”) Conversely, story songs, or songs with pithy lyrics and/or complex arrangements, might be difficult to sell to a dancing audience. Yet the same songs should work quite well with a listening audience. Regardless, be appropriate to what the venue proprietors and the audience that frequents that venue are expecting.

Key

The key of a song is its tonic chord: E, C#, Am, etc. The rule of thumb for a song’s key center is do not play more than two songs in the same key in a row. Although an audience might not be able to put into words why a band “kind of sounds all the same,” the foundation for that response is having too many songs in the same key played in a row.

Importantly, note that every key has a subtle but quite real sound quality. This is a function of sound waves and how they fit within the scope of equal temperament, the tuning concept that was adapted by Western music a few hundred years ago. Equal temperament is a tuning compromise that allows fixed-pitched instruments (piano, harpsichords, etc.) to sound “in tune” across many keys. The physics behind this concept have to do with harmonic overtones that sound when a note is played. For instance, take the fundamental A sounding at 440 hertz (Hz). The overtone series that sounds above 440 include 880Hz and 1760Hz. Play a Bb, however, and both the fundamental frequency and overtone series are, as you would expect, different than those sounding with A.

To get an insight into the veracity behind this concept, try this exercise espoused by the ear training professionals at perfectpitch.com: sit at a piano with a box of crayons and a sheet of paper with a grid that includes all twelve keys (C natural through B natural). Close your eyes and play each note in turn, in any order. Listen closely, think in terms of color, then literally find that color in your box of crayons and use it to fill in the grid next to the key center. When you have finished all twelve keys, you might be surprised by the heat (red or orange) or coolness (blue or green) that seem to emanate from each key center.

A good set list, then, mixes up the tonal centers. Moreover, it keeps track of minor keys, regardless of tonal center. Too many songs in minor keys in a row can also have a detrimental effect on an audience. If when you create your next set list you incorporate only this one concept of separating keys, your audience’s ears should remain alert and engaged throughout the performance.

Getting back to “color,” if you are one of those people especially sensitive to tonal centers, also keep in mind that an audience is only going to respond so many times to “heat,” so many times to “coolness.” If you play too many consecutive “hot” or “cool” songs the impact of either lessens. A truly well-crafted set list balances heat and coolness and all the key “colors” in between.

And finally, especially helpful to a good set list are songs in non-guitar keys like F-sharp, B-flat, E-flat minor, etc. One or two scattered about the set can really help a good set list’s tonal balance. (Conversely, for a horn band already playing in non-guitar keys, a few songs in guitar-friendly keys will help add tonal balance.)

Tempo

Tempo is literally a song’s metronomic setting. Most rock and pop music falls into one of three general tempo categories: slow (between 60 to 80 beats per minute), mid (between 80 and 112 beats per minute), and fast (everything above 112 beats per minute). Obviously, a good set list mixes up the tempos in the same way it considers key. Play too many mid tempo songs in a row and your audience will grow restless, sensing something is “off,” but not quite knowing why. This is a performer’s death knell. If your audience finds itself questioning, not responding, to your music, you lose them.

Especially off-putting to an audience is the double combo whammy of playing too many same tempo songs in the same key. If you want to witness an audience go brain numb right in front of your eyes, play three mid-tempo songs in the key of B-minor in a row. Regardless of the lyric content, which may be wildly diverse, your audience, while not being able to put their finger on why, will be undoubtedly be convinced that everything you play sounds the same.

Note that an argument could be made for a fourth tempo category: very fast, or tempos over 140 beats per minute. For an average folk, rock or pop act, this is probably an unnecessary extra step to consider, but for a band that plays a lot of fast songs, it does become important. A punk band, for instance, might not have any material that falls into the slow or mid tempo ranges, or maybe just one or two. In this case a finer honing of the tempos is important. If 90 percent of the songs in an act’s repertoire are above 112 beats per minutes, then mix the tempos into fast, faster, and fastest. And if one mid tempo song does exist, that one can be very effective in setting off the others. If key centers are also kept in mind, then an engaging, professional set list is still easily within reach.

Feel

Closely related to tempo is feel, the rhythmic nuance of a song. Is it a shuffle? Straight rock? Reggae? Sixites pop? A song with a given tempo could have any one of these feels. Played back-to-back, a song with a tempo of 112 beats per minute with a disco feel could sound entirely different from a song with the same beats per minute but played as a shuffle. This is especially true if the two songs are in different keys. But don’t push your luck. You might get away with sequencing three songs with the same tempo but with different feels and keys one after the other, but any more than that would start pushing the “why does this band sound all the same?” envelop too far.

(Note: regardless of Feel or Tempo, when it comes to Key two songs in a row should be a hard and fast rule. Just don’t do it.)

Transitions

A transition is the method and/or methods a band uses to get from one song to the next. Maybe it’s the drummer counting with his sticks, maybe it’s the front person shouting out the count Bruce Springsteen style. Maybe it’s funny/poignant story told from the stage about the origins of the next song. Hopefully it isn’t the band members looking around at each other saying, “What’s next?” or “How does this one start?” That kind of dead air can kill a performance. You don’t have to blitz from one song to the next. Especially if you are getting a good response, a lot of applause and whooping, both you and your audience want to bask in the communal glory for a few seconds. But as soon as that excitement starts to wane, to quote Ren Hoek, “Get on with it, man!”

Closely akin to Transitions are segues, which are pre-arranged, usually clever, transitions from one song to the next. Similar to medleys, which are transitions between snippets of songs, segues are song-to-song transitions. For instance, my band segues between two cover songs we play. We end “Times like These” by the Foo Fighters (Key of D) on a C chord. After an appropriate number seconds (different every time based on audience reaction) I play the opening riff to “Peace Train” by Cat Stevens, whose tonal center is C. Besides the different tonal centers, the songs have different feels, different tempos. We certainly don’t have our entire set segued, but we do have a few clever moments like this, which just add to the professionalism to which we strive.

Unless your group is playing Las Vegas-type shows, which are usually segued from top to bottom, a couple of two- or three-song transition clusters scattered about a set are handy for helping create a set’s sense of flow and excitement.

Timbres/Voice(s)

Timbre is the quality of a sound. A middle C, for instance, played on different instruments (piano, trumpet, harmonica, etc.) will be easily distinguishable from one another based wholly on the instrument’s timbre. This is equally true for the human voice—which non-coincidentally voice coaches refer to as a singer’s instrument. Each voice has a distinct timbre, just as non-voice instruments do. Yet singers can also modify their singing styles, switching from growl to croon to shout, etc. When it comes to your set list, this issue also needs to be considered. Just as with the previous concerns of key and tempo, too many shouting songs in a row can cause your audience to tune out.

And if you have the luxury of more than one lead singer in your group, your set list should be mindful of this as well. You might, for instance, have a singer who belts and one that croons. Neither style is inherently better than the other, but using them as contrasts can vary a set list nicely. After a shouter of a song, changing the tempo and key, then bringing in your crooner not only creates variety, it also propels your set forward, keeping your audience engaged, their ears satisfied.

Contingencies

This final section could have been entitled “Shit Happens.” You break a string. An instrument gets unplugged. A drink is spilled. Any one of these or a million other occurrences can obviously effect your set. To keep things rolling, what do you do?

First and foremost, panic never solves problems, so take a deep breath. Then consider contingencies.

You break a string. Can the rhythm section vamp the beginning of the next song while you quickly replace that B string? I’ve seen guitar players do this while actually talking to the audience, making light of the situation. Importantly, if breaking strings is something that happens to you on even a semi-regular basis, you should have string singles and whatever tools you need readily at hand. Or simply have a back-up guitar, in a stand, pre-tuned and ready to plug in. (If you do keep a back-up guitar on hand, please also pay close attention to the next paragraph.)

An instrument gets unplugged. Similar to a vamp, can you comp a rhythm sans bass? The disco band Chic was famous for their no bass sections, the rhythm guitar, drums and percussion propelling the song forward. Most importantly, if you’re the bass player, please do turn down your amp before you start searching for the plug, thus avoiding the obnoxious electronic zap! when you finally do re-plug in the cord.

A drink gets spilled. If you’re a drinking band, have some bar towels, both damp and dry, scattered about the stage for such emergencies. Clean up quick, engage the audience with some clever banter about “party time,” etc., and then get on with it.

And sometimes, if the shit that’s happened is too much for a quick “during the set” fix, it’s also okay to let the audience know you’ve got an equipment malfunction and that you will be back just as soon as possible. And when you do return, it can be where you left off with your set, a melding of what’s left of set one and set two, or just starting up your second set from the top.

————

What do you think makes a great set list? Any criteria we haven’t considered? Let us know in the comments section below.

Author Bio: Gary McKinney is a musician, writer, editor, and publisher. He lives in Bellingham, Washington. His most recent novel is “Darkness Bids the Dead Goodbye,” a mystery featuring Sheriff Gavin Pruitt, Deadhead. “Slipknot” is the first of this mystery series. These and other books with a music theme can be found at: kearneystreetbooks.com. Gary’s band site is: fritzandthefreeloaders.com.

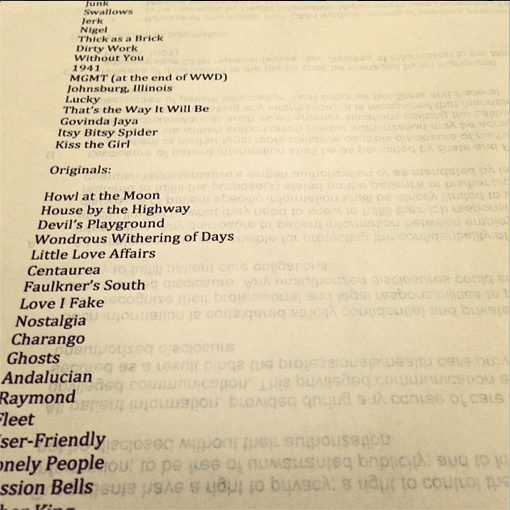

[Editor’s note: I’d like to mention that the same criteria mentioned below for live shows can help you determine the track listing for your next album. The photo is of a list I made for a recent 3-hour solo gig — BEFORE deciding on the order of the songs.]

For information about booking gigs and planning successful DIY tours, download our FREE guide:

[hana-code-insert name=’touring-book-your-own’ /]